Tao That Can Tao Is Not Always Tao

Tao Te Ching: Chapter 1

As you may know, translation is an important component of my mission here at markwillwrite. Among all of my books, the translations are my best-sellers (though of course that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t also sample a work of literary fiction, a travelogue, and/or a volume of poetry). Readers have found my translation of Aeschylus’ Persians to be of contemporary relevance in light of the West’s ongoing harassment of Iran. My English rendering of Fernando Pessoa’s Message has proven to be popular with fans of the Portuguese master’s more well-known Book of Disquiet. As mentioned in a previous post, this translation of Message, while available through my own Cadmus & Harmony Media imprint as a paperback, ebook, and audiobook, is also sold in a deluxe hardcover edition at Café A Brasileira in Lisbon, Portugal.

I recently noted in passing that I have begun work on an “infidel translation” of the Gospel According to Mark as well. And today, as if I were not busy enough, I am pleased to announce that I have also started translating the Chinese classic known as the Tao Te Ching. Now, lest you protest that a lao wai such as myself has no business interpreting this ancient Chinese text, I hereby state for the record that I quite agree with you. Indeed, I freely admit that I have no right to undertake such a sacred task—particularly as I can lay claim to no expertise in the Chinese language (quite the contrary, in fact: 我的中文不好). However, this does not deter me from attempting the impossible. Fortunately, though, I am not bearing the workload alone, inasmuch as I have wisely enlisted the aid and assistance of Dr. Hong Zhi-Ping, a Taiwan-based scholar and a native speaker of Mandarin. Together, as collaborators on this quixotic project, we have discovered a very effective means of rendering the ancient Chinese into modern English. Allow me to explain.

The Method

For each chapter of the Tao Te Ching, we follow 5 simple steps:

Read the original. Together Dr. Hong and I are reading the standard prose version of the Chinese text, as established by Wang Bi in the third century CE. We analyze the grammar, syntax, and diction until we have a clear understanding of each character in the text as well as its relation to all the other characters. This is obviously the most difficult and painstaking step, even for native speakers of Mandarin like Dr. Hong.

Identify key words and phrases. There are certain key words and phrases which recur throughout the 81 chapters of the Tao Te Ching. We will make an effort to identify, translate, and explain these concepts and highlight them in the notes to our translations.

Translate line by line. After rearranging Wang Bi’s prose text into lines and stanzas of poetry, we proceed to translate as literally as possible into English, one line at a time.

Compare other translations. Having hammered out a rough literal translation, we then consult 5 other English renderings of the text during the revision process. The 5 translations, in no particular order of importance, are those by (1) Stephen Mitchell, (2) Derek Lin, (3) Aleister Crowley, (4) Ursula K. Le Guin, and (5) Gia-Fu Feng/Jane English.

Finalize. Having followed all of the previous steps, we eventually arrive at our final translation of each chapter.

This of course is a recursive process, which may be applied somewhat differently to each chapter of the Tao Te Ching. But let’s see how it works with Chapter 1, shall we?

The Original

As mentioned above, our text is the Wang Bi prose version. Chapter 1 reads as follows:

道可道,非常道。名可名,非常名。無名天地之始;有名萬物之母。故常無欲,以觀其妙;常有欲,以觀其徼。此兩者,同出而異名,同謂之玄。玄之又玄,衆妙之門。

Key Concepts

In the Chinese text of Chapter 1, we identified several key words and phrases. To wit:

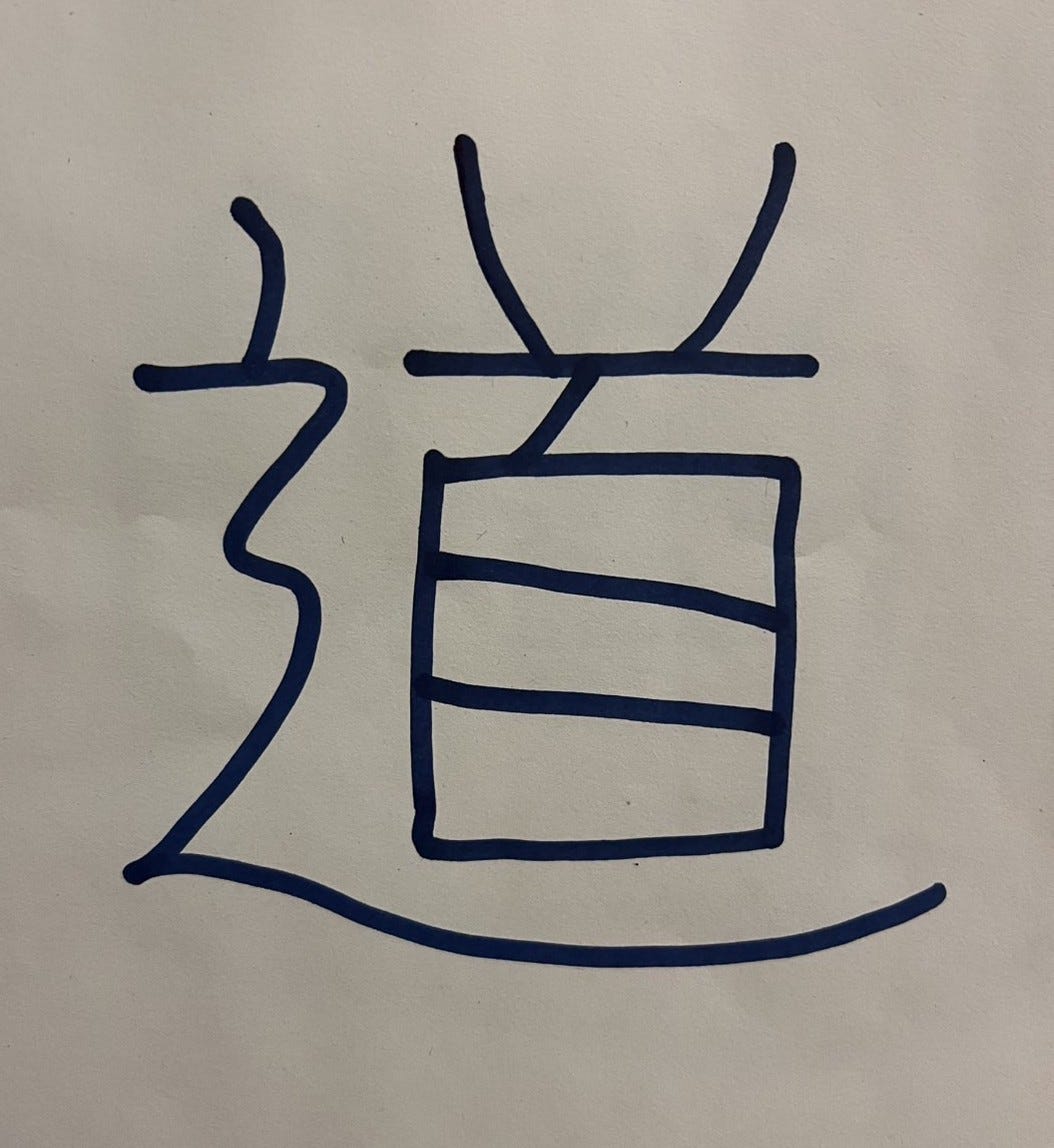

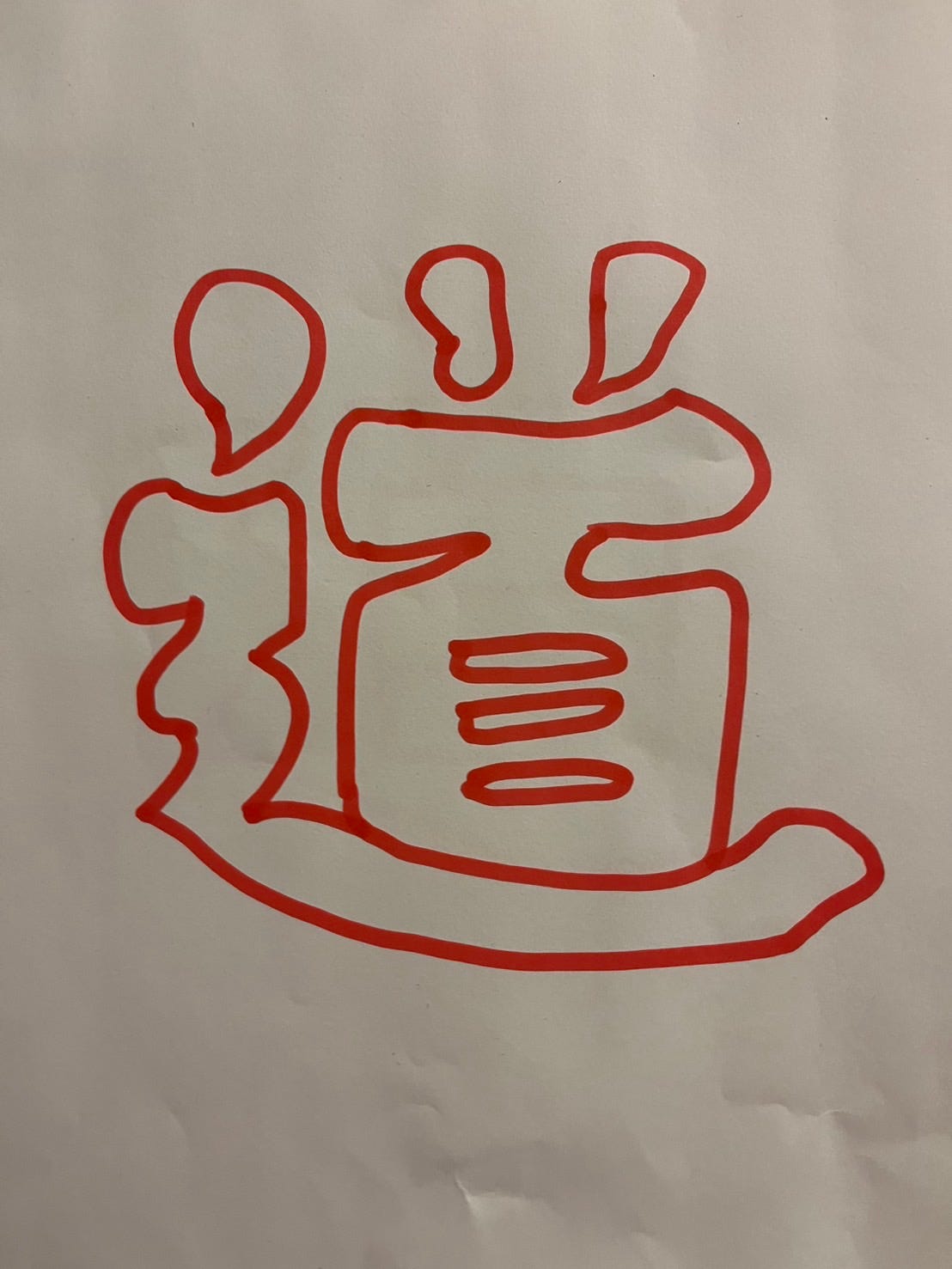

道 (Dào, but traditionally spelled Tao) - obviously the most important concept in Chapter 1 and indeed the entire book; translated variously as road, way, path, talk, say

名 (míng) - name(s)

天地 (tiāndì) - literally, Sky-Earth or Heaven-Earth; translated in our version of the text as Heaven and Earth; more generally, it can mean the World

萬物 (wànwù) - literally, Ten Thousand Things; more generally, it can mean Everything

常 (cháng) - always, often, eternal; when coupled with 非 (fei) in the phrase 非常 it means not always (or, in modern parlance, very)

欲 (yù) - want, desire

妙 (miào) - wonderful, splendid

玄 (xuán) - mysterious

N.B. In Chinese, parts of speech are somewhat fluid. The same word may function as noun, verb, or adjective, depending on the context.

Line by Line Layout

Intuitively, we then rearranged the prose version of Wang Bi’s text to resemble poetry. In the case of Chapter 1, we decided on four stanzas, guided by the sound and sense of the text. Thus:

道可道,非常道。 名可名,非常名。 無名天地之始; 有名萬物之母。 故常無欲,以觀其妙; 常有欲,以觀其徼。 此兩者,同出而異名, 同謂之玄。 玄之又玄, 衆妙之門。

Comparison of Other Translations

After hammering out a rough literal translation of the foregoing, we consulted the other English versions. The introduction to Aleister Crowley’s edition of the text proved instructive in the case of Chapter 1. He describes some of the difficulties encountered by those who are foolish enough to attempt to translate the Tao Te Ching into English:

The very first word ‘Tao’ presented a completely insoluble problem. It had been translated ‘Reason,’ ‘the Way,’ ‘TO ON’ [by which he means the Platonic τὸ ὄν or Being]. None of these convey the faintest conception of the Tao.

Crowley offers to remedy this defect by translating the first line of Chapter 1 as follows:

The Tao-Path is not the All-Tao.

We ourselves simplify things even further by translating 道 as Tao when it appears as a noun and tao when it appears as a verb.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s understanding of Chapter 1 also proved relevant to our process. In a note which appears after her translation she writes:

A perfect translation of this chapter is, I believe, perfectly impossible. It contains the book. I think of it as the Aleph, in Borges’ story: if you see it rightly, it contains everything.

Interestingly, she titles her translation of Chapter 1 “Taoing”—a verbal noun which highlights the active component of Tao which is reflected in our translation as well.

Final Translation

And so here’s what we ended up with, the final version (for now) of our idiosyncratic English translation of Chapter 1 of the Tao Te Ching:

Tao that can tao is not always Tao. Names that can name are not always names. Nameless is Heaven and Earth's source. Named is Ten Thousand Thing's mother. Thus, always desireless, one sees the essence. Always desiring, one sees the form. These two have the same origin but different names. Together they are called Mystery, Mystery of Mysteries, Many Wonders' Gate.

Going forward, our plan is to translate 1-2 chapters per week until we have completed all 81. We hope to include artwork and/or photography with each chapter in the final book version of our translation, having been inspired by the Gia-Fu Feng/Jane English edition (about which Alan Watts said: “No one has done better in conveying Lao Tsu’s simple and laconic style of writing, so as to produce an English version almost as suggestive of the many meanings intended. This is a most useful, as well as beautiful, volume—and what it has to say is exactly what the world, in its present state, needs to hear.”) Also, there will be notes and commentary on each chapter in the back of the book, such as may be found in Derek Lin’s excellent version of the text. Stay tuned for our rendering of Chapter 2, and in the meantime let us know what you think of this new translation project.